It has been an unprecedented and taxing two years for front-line workers and patients alike. Nearly one of three patients delayed in-person health care visits in 2020 due to access issues and/or fear of exposure to COVID-19. According to a national poll, 57% of Americans experienced negative health repercussions, including and up to premature death.

In March 2020 the passage of an emergency declaration under the Stafford Act1 marked a profound transformation in the landscape of eHealth2 to support providers and patients as a public health policy measure during the pandemic. This federal initiative not only promoted the expansion of telehealth for all Medicare beneficiaries, but also included waivers for more provider types to offer more comprehensive services ranging from wellness visits and hospice care to inpatient rehabilitation and stroke management. Subsequently, e-visit compensation was equivalent to in-person office visits, with no restrictions placed on patient location. During the last week of April 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported that almost 1.7 million Medicare recipients participated in a telemedicine visit, compared to approximately 13,000 telemedicine encounters in a week prior to the expansion.

What are the opportunities and obstacles associated with digital health services?

Table 1:

| Opportunities: | Obstacles: |

|---|---|

| Increase access to care | Technology inexperience by some patients and practitioners |

| Decrease cost | Decrease continuity of care |

| Promote continuity of care | Reduce patient engagement and changes in expectations |

| Improve patient self-management | Limitations for deaf, hard of hearing, blind, visually impaired, ESL, or other vulnerable populations |

| Efficient care delivery (shorter wait times, shorter consultations, and fewer missed appointments) | Limited or no access to broadband |

| Prevention of treatment-related errors such as medication errors | Difficulty in establishing a diagnosis without physical exam and other non-verbal signals |

| More timely diagnosis and treatment | Increase in medical errors and cost |

| Improve patient-provider communication and facilitate therapeutic relationship | Decrease in confidentiality during consultations |

| Limit patient exposure to COVID-19 | Weakening of therapeutic relationship due to “depersonalization practice” of remote care |

| Conserve use of PPE | Decrease team building among the care team |

| Providers able to see patients more frequently when necessary | Providers have less time to complete their notes and follow-up due to obstacles in learning how to navigate video consultations and use of EMR3 |

| Providers have more time to complete their encounter notes | |

| Increase flexibility in provider scheduling and availability | |

| Improve practitioner medical history information gathering documentation and subsequent diagnostic skills |

Based on Table 1, the answer to this question depends largely on where one stands in proximity to digital domain knowledge and access, and if there is an inherent disability impairment.

While we continue to chart a course through this new terrain, for many individuals telehealth has proven to be a convenient tool to increase care delivery efficiency, decrease infectious disease exposure, and address supply side constraints (PPE, staffing, and other resources) that are driven by demand surges. However, for others, remote care brings measurable risk by increasing disparities in care due to a lack of appropriate equipment or sketchy internet service.4

To examine the limitations and to further understand the challenges of remote care, we mined safety data reports from the CHPSO database. There were a total of 117 cases in the final sample from 2018-21 (initial report date) with 80% taking place outside of acute care and the clinic settings and 20% in diverse facility settings. Approximately 46% of the cases were events that reached the patient where harm may or may not have occurred, while 43% of the cases were considered unsafe5, and 7% were near misses (4% were null). The tables below provide the sample dataset demographics. There were slightly more females (40%) than males (37%), with adults (40%) making up the largest age group, followed by children (16%), and mature adults (9%), with the last three groups of adolescent, older adults, and aged adults accounting for the remaining 7% combined (27% were null).

| Gender | Count |

|---|---|

| F | 48 |

| M | 43 |

| NULL | 26 |

| Age Range | Description | Count |

|---|---|---|

| 18-64 | Adult | 47 |

| 1-12 | Child | 19 |

| 65-74 | Mature Adult | 11 |

| 85+ | Aged Adult | 4 |

| 13-17 | Adolescent | 2 |

| 75-84 | Older Adult | 2 |

| NULL | 32 |

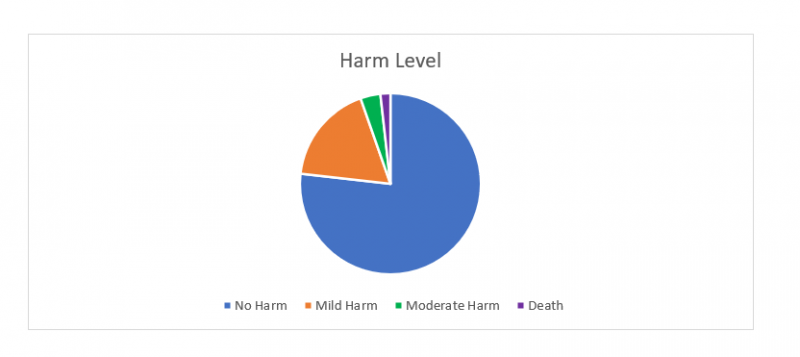

The level of harm data in the pie chart below indicates that the majority of these events were labeled as No Harm. There was, however, one death involving a post-surgical case. The patient received a new diagnosis of arrhythmia following surgery and during two separate post-hospital discharge telehealth visits no complaints or concerns were voiced by the patient. The patient later expired in the emergency department.

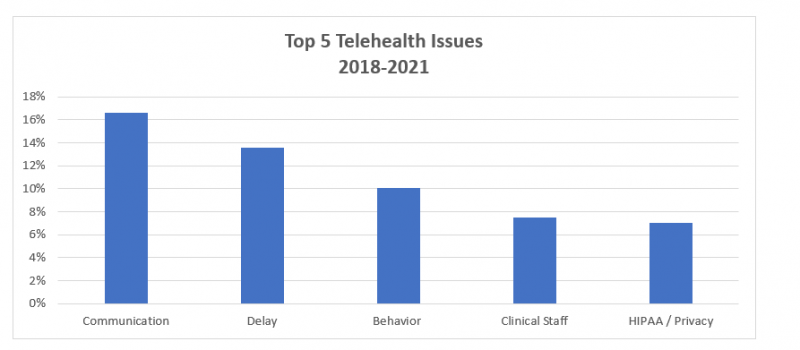

These events were aggregated based on similar safety issues and ontological patterns identified across the data and include specific associated factors to provide more granularity. For example, danger to self or others events were often linked to law enforcement involvement. Likewise, a single event may have been labeled with multiple themes/issues and consequently the issue totals may exceed the number of unique events.

Communication was the top issue and was commonly associated with missed visits. Causes of missed visits included provider or patient no-show, the clinic not having the correct patient phone number for virtual check-in (which resulted in a failure to connect), and lastly, the support staff failing to inform the provider of scheduled virtual visit. Moreover, scheduling confusion contributed to missed visits and consequently a delay in treatment. In several instances, patients spent several hours in the virtual waiting room for a pre-arranged telehealth appointment, but no contact was made by the care team. These individuals later learned they were classified as a “no show” and the appointment was canceled altogether.

Delay or lack of response was the second-most common event and frequently linked to mental health visits, follow-up care, and insurance issues. A considerable proportion of mental health visit types were intractable situations where coverage for consultation was unavailable or lacking for the requested timeline. Specifically, weekend coverage was unavailable in most of these cases with many services delayed until the following Monday.

By the same token, follow-up care and insurance verification were sometimes intertwined. Insurance verification was either not completed prior to the scheduled telehealth appointment so the visit could not proceed, or the follow-up visit did not occur due to failure to connect virtually — together these two patient safety events comprised roughly 63% of all the delayed cases. As an example, in one case, the patient was upset about the delay and refused to communicate with the care team despite attempts to correct the situation by the service recovery staff. The patient may have ultimately slipped through the cracks as there was no primary care provider on file for follow-up care.

As might be expected, behavior-related events often followed delays, the third-most common category. Examination of several behavior events seems to suggest that not understanding virtual care workflow or non-compliance with the workflow or perhaps having different expectations with virtual care may all be contributing factors. Verbal threats, name calling, and non-compliance toward the support staff were frequent behaviors reported as the staff attempted to complete the virtual check-in. Other contributing factors include patients experiencing technical difficulties navigating in the virtual environment and an implied sense that there could be more of an improvement in care if visits were managed in-person rather than virtually. This may suggest that for some patients, telehealth is seen as a barrier to optimal care and therefore not a viable option.

The fourth-most common event, clinical staff, is related to three primary areas: telehealth workflow, patient location, and physician privileges. In each of these cases, protocol was not followed. For example, the support staff did not schedule the correct meeting duration for a specific type of visit (e.g., hospital follow-up visits are a minimum of 30 minutes, longer visits for patients with language barriers, etc.); the provider did not allow support staff to complete virtual check-in, so documentation was incomplete; the provider failed to include the location where the patient was for the telehealth visit6; or there was a concern about state-regulated physician practice.

Lastly, HIPAA cases were predominantly associated with technology issues such as software bugs that allowed a patient to enter a virtual meeting at the same time one was occurring with another patient — a violation of privacy regulation; email communications revealing email addresses of everyone in the distribution list instead of using BCC; Zoom links sent to the wrong patients; documents from one patient incorrectly emailed to another patient; and unexpected family members present in the virtual visit.

With the early and rapid adoption of video conferencing as a means of providing distance health services, it’s important to remember we are still assessing the overall impact of telehealth on patient safety. Although small-scale studies have limitations and a small dataset precludes us from fully understanding the impact on safety, we can still gain some insights from this analytical process.

So, what are some of the lessons learned?

- From a patient perspective, remote care may not be optimal for everyone, especially for those with barriers to technology.

- From a provider perspective, it’s important to recognize technology knowledge gaps and address them. It’s also vital to acknowledge the limitations imposed on diagnostic capabilities in the context of delivering care from a distance. More training is needed for practitioners on best practices and guidelines when care is delivered using video conferencing platforms.

- Telehealth should never be a substitute for in-person visits, but a complementary service to delivering care.

- Other processes should be built into remote care such as escalation algorithms to determine when to shift from a virtual visit to an in-person visit and performing a deeper dive into which individuals would benefit most from telehealth services vs. which individuals should be seen in-person.

- Improvement can be made to existing core workflow processes. This includes scheduling issues, following strict protocols for items such as insurance verification prior to the virtual visit to minimize delays and curtail behavior issues, and closing fundamental data gaps in patient contact phone numbers and primary care provider information to prevent cancellations and reinforce continuity of care.

- Weekend coverage should be provided for a mental health evaluation to assure there are no delays in treatment or no barriers in accessing care.

There is much more to learn, especially the long-term effects and how equity and inclusion fit in this delivery system.

1 https://sgp.fas.org/crs/homesec/R46809.pdf

2 While it is common to hear telemedicine, telehealth, and virtual care used interchangeably, do they all mean the same? According to the Health Resources and Services Administration, telehealth denotes activities with a broader scope, while telemedicine distinctly refers to remote clinical services only. On the other hand, virtual care is considered a subset of telehealth and uses a variety of different platforms, including instant messaging.

3 https://bmcprimcare.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-021-01543-4

4 A visit type study of ambulatory health centers for services provided to 30 million low-income patients in California conducted by Uscher-Pines and colleagues reported that 48.5% were by telephone, 3.4% by video, and 48.1% were in person visits from March to August 2020. A higher rate of telephone visits infers reduced access to the proper technology for video conferencing and/or knowledge gaps in computer use.

5 Circumstances that increase the probability of a patient safety event (AHRQ Common Formats)

6 Billing requirements state must include documentation of the location of the patient receiving the virtual service as best practice.